The Rugby School Registers

Holly Hiscox (Open University)

Introduction

This blog post explores some of the ways in which The Registers of Rugby School — a key source contained in the Rugby Archives — has been instrumental in shaping some of my initial doctoral research. To set the discussion of this particular source in context, this post begins with a brief summary of my project with the intention of outlining the backdrop to the particular analysis that I’ve been undertaking.

The working title of my PhD study is ‘Public schools, empire and the City of London, c.1828-1914: Rugby School and the making of an imperial financial elite.’ My project proposes to use Rugby School as a case study to explore the relationship between public schools, empire, and the formation of Britain’s financial elites in the City of London. Its aim is to shed new light on the complex interrelations between three institutions – public schools, the City, and the empire – which have been central to the reproduction of Britain’s elites and global patterns of inequality since the mid-19th century. Given the scale of the task, my thesis will use Rugby School as a case study, employing a prosopographical analysis of a cohort of its pupils to illuminate wider themes and developments central to the project.

The Rugby School registers – an overview

The Rugby School registers have formed a crucial source during the early stages of my research. At a basic level, the registers provide a record of pupils who were admitted to the school and their year of entry. The registers cover the vast majority of Rugby School’s history and full registers are available from 1675 to 1946 (Rugby was founded as a free grammar school in 1567). Whilst physical copies of the register exist in the archives at Rugby, these sources have also been digitized, making them more accessible for researchers.

Another useful aspect of the registers is the fact that they are ‘annotated’. This means that some records have been updated with further information about what the individual pupils went on to do in their future lives, for example in terms of university education or career. The bulk of this work was completed by an Old Rugbeian, A. T. Michell, and the two volumes that cover my period of interest were completed in 1901 and 1902 respectively. These different facets of the registers make them a rich source of evidence for historical analysis, and one in which I have drawn on heavily in the initial stages of my research.

The Rugby School Registers – an example.

The adjacent image is an example of a section of the school registers. This particular extract shows the details of four pupils who entered the school in August 1832.

It is possible to see that the registers give the pupil’s name, the name of their father (or name of mother if the father was deceased) and a home address. Occasionally there’s also information that can be gleaned about the family – for example,

here for John Wasey we know that his father was a Reverend, and in other examples references to a father’s title, landed estate, or overseas home address are given. The pupil’s age and birthdate are shown, and this can give us some clues about the length of time a pupil spent at Rugby, although this should be placed in the context of the nature of education at the time, where pupils were grouped into classes by academic ability rather than calendar age.

Italicised, to the right hand side of this information, is the name of the school house that the pupil became a part of on entry to the school. This is important information because here we can begin to construct some of the details of an individual’s school life. We know immediately whether they were a day pupil or a boarder (Town house was for day pupils), and then by cross-referencing this with other sources – and indeed, other parts of the register – it becomes possible to piece together where they would have been accommodated at the school, who their housemaster might have been (for example School house shown here was Thomas Arnold’s boarding house), and who their contemporaries were within their house.

This is really crucial evidence, as within the wider structure of the school, the House system has been ascribed particular significance.[i] Several authors have noted how the school House provided boys with a form of identity and demanded a specific sort of loyalty from its members.[ii] Patrick Joyce argues, however, that the House system’s importance is of a magnitude not previously fully considered, and which goes beyond basic feelings of identification and allegiance. For Joyce the fact that the school house replaced the earliest experience of intimate home life is key, and helps to explain the ‘extraordinary hold’ that the public school had on the British ruling classes – and by extension, ‘British society more widely.’[iii] This view is echoed by P.J. Rich who asserts that the public school house was the only institution that could rival the family ‘in its intensity.’[iv] Joyce describes it as a ‘state in miniature’, which holds ‘enormous power’ and sees the spatial patterns of the school house replicated throughout the lives of elite men in the 19th century – for example, in the Oxbridge college, the gentlemen’s club or the government office.[v] In my research I hope to be able to use the individual house archives at Rugby to achieve a greater understanding of how pupils’ domestic experiences in their boarding Houses may have shaped their identities and wider outlook on life.

This information – name, family, address, age and school house — is present almost without exception for every pupil. What differs is the annotated element underneath. For some pupils there is no additional annotation, whilst for others extremely detailed summaries of their lives after leaving Rugby exist. The example you see here demonstrates this. We know that Henry Hucks Gibbs and John Wasey attended Oxford University, which is interesting in itself if we consider the Oxbridge College a further iteration of the public school boarding house. Yet what’s also especially noteworthy is the imperial connections which can be seen here as well. Two of the boys’ later lives are directly entwined with Empire – Fleming Malcolm Martin was in the Madras Army and was in active service during the Indian Uprising of 1857. William Cotton Fell emigrated to Australia and became a settler. Henry Hucks Gibbs is also an interesting case. It mentions in the registers that he became an MP for the City of London and was also a Director of the Bank of England. Given what we know about the close links between the City of London and imperial finance, this warranted further investigation, and by researching Gibbs in more depth, after the hints given here, it transpired that he became head of the his family firm, Antony Gibbs & Sons, a company heavily involved in trade in Britain’s ‘informal empire’ in South America, which reveals a further imperial link. Although only a small snapshot of the registers, the example of the four pupils above outlines some of the information that they yield, and the way in which this can open up new avenues of research.

The bigger picture

Whilst having the registers in a digitized format is really useful, I recognized that it would be beneficial to convert the key information into a format that would be more easily searchable, or which could be organized by different aspects, e.g. by school house, or by levels of involvement with Empire. I’ve started to construct a spreadsheet which will allow me to do these things, and although still under construction, I’m hoping that in the coming months this record will help as a reference point to organise the data gathered from these registers.

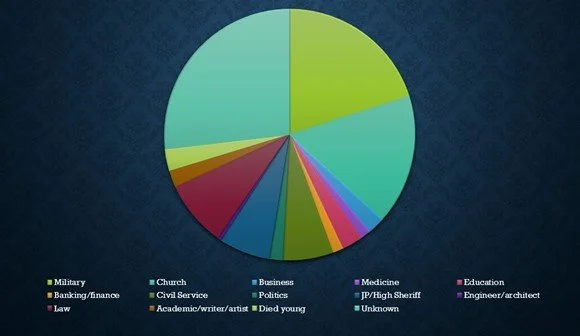

In an initial (and less detailed) data gathering exercise using the registers, I have looked at every pupil record from the beginning of Thomas Arnold’s headship in August 1828, to the end of Archibald Tait’s headship in the summer of 1848 and have completed a summary analysis of their adult occupations. Here I was interested in all the different adult activities and occupations listed on the register which means that the charts that follow are based on number of listed occupations rather than individuals. For example, it was not necessarily uncommon for an individual to have two or three different occupations listed in the registers, and here each is included. Whilst some of the occupations refer to renumerated activity or employment, others (such as being an MP or JP) do not, but are nonetheless included since they still denote important societal roles, despite the fact that undertaking them depended on having independent wealth. Altogether there were over 2,500 careers listed, and the different proportions of these are reflected in the charts that follow.

Occupations of all Rugbeians (school years 1828 – 1848)

This chart gives a snapshot of the different occupations of Rugbeians who were at the school during a twenty-year period beginning in 1828. Many of the careers are ones that you would expect for a 19th century public school, for example, military, law, and the Church. The relatively large number of ‘unknown’ (27%), where no additional information has been given in the annotated registers or only information about university attendance, is significant. This poses an issue when considering the entire pupil roll but is not necessarily an insurmountable problem for my own research, where I am most interested in using the registers to identify a specific cohort for close analysis. This overview of all the Rugbeians of this era also includes a proportion of Rugbeians who the registers state died before the age of 25, in the ‘died young’ segment.

Known occupations of Rugbeians 1828 - 1848

If we focus on the ‘known’ occupations of the Rugbeians of this period, it is clear to see that military, legal and Church careers do dominate, but significant numbers of former pupils could also be found in the civil service, in education (masters, headmasters, school inspectors), business (predominantly in Manchester and Liverpool, but also overseas), and in banking and financial services.

An Imperial School

The registers also offer important insights into the links between an education at Rugby School and future associations with the British Empire. Using the details from the annotated sections of the registers, it is possible to undertake a further layer of analysis to demonstrate Rugbeians with a direct link to the British Empire, including those who lived and worked in colonies spanning the globe. Of the ‘known’ occupations, those with direct imperial connections make up a significant proportion. Involvement in the military is very clearly the largest Empire related career path, and the details in the registers demonstrate many Rugbeians involved in various actions, but probably most prominently in India around the time of the 1857 Indian Uprising and in the Crimean war too – at the siege of Sevastopol and at Balaclava, for instance. A large proportion of Rugbeians were also ensconced in the Indian civil service, and Anthony Kirk-Greene in his analysis of the colonial civil service notes that Rugbeians were – in comparison to old boys from other public schools – especially heavily represented in this area of colonial administration.[vi] Business and banking were also significant areas. For example, some Rugbeians became tea and coffee planters in India and Sri Lanka, others were involved in financial services with imperial dimensions such as insurance underwriters at Lloyd’s, or directors of banks with considerable colonial interests, and these livelihoods were enmeshed in the web of imperial trade and finance.

Of course, attempting to separate out ‘empire’ and ‘non-empire’ careers is a somewhat artificial distinction, given the huge shadow that Britain’s imperial activity cast across the whole nation during the 19th century. In a sense, to use Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose’s term, all Briton’s were ‘at home’ with Empire.[vii] The utility of the registers in this respect is that they can provide a basic overview of those pupils whose everyday professional lives were directly and consciously linked to empire, but the glaring limitation is that this is too simplistic a representation to fully capture the true complexity of all individuals’ involvement with empire.

The Rugby School registers – identifying a cohort.

One of the most significant aspects of the availability of the registers as source is that they have enabled me to identify a cohort of pupils who were at the school in a twenty-two year period between 1828 and 1850 who later worked in the City of London, and it is these individuals that will form the basis of my study. For some of them this means that their time at school coincided, which meant that they would have known each other, and in some cases lived in the same boarding house as each other from a young age. Even if their time at Rugby didn’t overlap, they were still exposed to the same types of routines, lessons, values and ethos across the period, and had professional and social connections with each other in adult life.

Beyond these individual lives, a consideration of the parentage and wider family background of the 1828–1850 ‘financial’ Rugby cohort is also an important area of investigation in tracing the links to family firms and imperial connections, and reconstructing early formative influences. The extent to which money made from overseas banking and finance paid for a Rugby education is significant, as is the inter-generational commitment to education at the school. For example, George Carr Glyn sent three of his sons to Rugby School, presumably using wealth generated by the family bank of Glyn, Mills & Co. Many of the other Rugbeians at school between 1828 and 1850 and who later entered careers in the City of London were members of families who already had established firms and businesses with overseas interests – for example, Henry Hucks Gibbs (Antony Gibbs & Sons), George Goschen (Fruhling & Goschen), Henry William Lindow (his family were recipients of a significant amount of slavery compensations), Samuel George Smith (Smith, Payne & Smith), Edward Charles Baring (Barings Bank) and Frederick Cazenove (Cazenove stockbrokers). An education at Rugby also spanned several generations for some familieis – for example, the Lindows (formerly Rawlinsons) comprise a number of generations of Rugbeians dating far back into the 18th century, and George Goschen elected to send his own son to Rugby in 1881.

Image: From left to right, Henry Hucks Gibbs, George Goschen, and Edward Charles Baring. (Image Credit: Wikipedia)